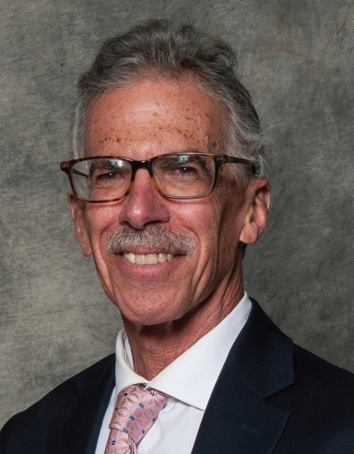

Led by Nathaniel Diskint (center), Cohome is a Morristown-based nonprofit that partners with developers to create inclusive housing projects for adults with special needs. — Photo by Aaron Houston for Real Estate NJ

By Marlaina Cockcroft

There’s not enough supportive housing in New Jersey, according to advocates and industry experts, and they hope incentives in the state’s revamped affordable housing rules will help expand the market.

Supportive or special needs housing includes modifications for residents with physical disabilities — such as a wider bathroom or lowered faucets to accommodate a wheelchair — or social services for residents with autism, depression or other behavioral challenges so that they’re able to live independently.

New Jersey’s new affordable housing law, which was enacted in 2024, created a framework to address each municipality’s unmet need of low- and moderate-income homes under the 1985 Fair Housing Act. As part of the law’s so-called fourth round, from 2025 to 2035, municipalities can receive bonus credits against their obligations if they reserve some affordable units as supportive housing.

Proponents say the incentive should increase the stock of supportive housing statewide. The remaining question is how to raise awareness and ensure that developers and municipalities are taking advantage of the new program.

“We need all types of affordable housing in New Jersey to serve all different types of populations,” said Nathaniel Diskint, executive director of Cohome, which partners with developers to create inclusive residential projects for adults with special needs. “But with these bonus credits, it’s kind of a no-brainer. If you have an opportunity to create supportive housing, developers should certainly consider that.”

Generally speaking, the law provides towns with one and a half or two bonus credits against their fair share obligations for projects that involve age-restricted homes, units for individuals with special needs and housing near mass transit, among other scenarios. Diskint is now working to spread the word, citing a conversation with a developer that is mulling whether to use supportive housing in a project in Essex County, amplifying the impact of its three affordable units.

Cohome has engaged another developer about a 300-unit project near Cherry Hill with 50 affordable housing units, 25 of which are supportive housing, he said. This could become the largest supportive housing project in the state.

“I think there’s definitely an unmet need, and I think there’s especially an unmet need for people who have intellectual disabilities, autism spectrum conditions,” said Cory Storch, CEO and president of Bridgeway Behavioral Health Services, which provides services to residents in supportive housing units. Importantly, he added, the supportive home model “helps people stay out of more expensive services like hospitals and emergency departments.”

Diskint said the official Medicaid waitlist contains about 8,000 people with intellectual and developmental disabilities looking for housing, but he thinks the actual number is higher. That makes it all the more important to expand supportive housing in New Jersey, he said, noting that such projects can garner support from communities.

“It doesn’t come with that perception that you’d be bringing in a new population,” Diskint said. “You’re just giving existing neighbors a better opportunity to live independently. Disability affects all populations equally.”

Christiana Foglio, founder and CEO of Community Investment Strategies, said towns might have hesitated to add supportive housing in the past due to NIMBYism or a “not in my backyard” pushback. But incentivizing municipalities means “you get everybody on the same page.”

She thinks that including supportive units, as her Lawrenceville-based firm does in all of its affordable housing projects, helps get the developments approved, she said. She added that, when CIS incorporates special needs housing, it knows in advance which homes it will build to accessible specifications. For residents with mental health issues, the developer pays a nonprofit to provide support services and check-ins.

State funding has been a major factor in increasing supportive housing, said Melanie Walter, executive director of the New Jersey Housing and Mortgage Finance Agency. The Special Needs Housing Trust Fund has long provided loans to developers and governments to create the projects, but the funding was mostly gone by 2018, slowing development. In 2021, the state Legislature recapitalized the fund at $20 million a year.

Walter said, now that the funding is assured, it’s getting built into developers’ plans.

“Since 2021, we saw a 28 percent increase in supportive housing beds and individuals assisted in each of the first two years, and then in 2023, it went up even more — 84 percent,” she said. “And that was because (with) a lot of the federal programs, we required that there be at least five special needs apartments vouchered in each new building that was built.”

Between 2010 and 2020, there were 120 to 300 new supportive units produced a year in New Jersey, but now Walter expects that number to jump to 580 to 600.

Still, advocates and developers grapple with another challenge. Foglio notes that supportive housing residents might only have $400 or $500 to spend on rent.

“I think the saddest part is when we build the special needs units … that they go unused because you can’t find people that can afford to live there,” she said.

While the State Rental Assistance Program does assist disabled households, Foglio doesn’t expect much federal help. State and other organizations need to determine “how do we really wrap around people of need at this level, special needs in particular, to try to figure out how we actually get them in units that now we can build.”

Especially with the impact that the projects have demonstrated in the past.

“We see phenomenal outcomes,” Walter said. “We see very low eviction rates. We see a lot of improvements in terms of care and medication compliance and physical and occupational therapy … When we take that holistic approach and you have the landlords responsible for providing social services and the town’s invested in that resource, we’re really helping a lot of individuals who would have struggled in a lot of housing markets around the country.”

Marlaina Cockcroft is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.