A rendering of the 100-acre Bayfront project on the west side of Jersey City — Courtesy: Dattner Architects / Synoesis

By Joshua Burd

For Jersey City Mayor Steve Fulop, it was a point worth noting: The city wasn’t going to let a pandemic stop it from moving forward with a critical development project, especially one that he says will be the largest new infusion of mixed-income housing in the tristate region.

It’s why he and his team seized the chance in early June to announce the first phase of the 100-acre Bayfront project, which will ultimately bring 8,000 units to the city’s west side. After all, the development is several years in the making and — despite the virtual statewide shutdown since mid-March — city officials have been moving forward with the details of design, engineering, financing and negotiation with its would-be developers.

“There’s been a lot of moving parts over the last three months,” Fulop said of Bayfront, which will include 35 percent affordable housing at a site just west of Route 440. “This wasn’t ready to go in January or February … but we did push harder in the last three months because we knew we were on the right track with what the city wants to see and the residents want to see with regard to development in the future.”

As it turns out, the coronavirus isn’t stopping much else in Jersey City’s development pipeline. While local officials across New Jersey have hit the brakes on large-scale projects, the city has made a deliberate effort to keep its pipeline flowing since the start of the health and economic crisis, as many developers remain bullish on its booming residential market.

“Jersey City has always been out front — and advanced and cutting-edge — when it comes to the whole development program,” said W. Nevins McCann, an attorney with Connell Foley LLP, who co-chairs the firm’s real estate and land use group. “When you look at what’s happened in Jersey City over the last 25 years, it didn’t happen by accident.”

McCann, who represents many of the city’s most active developers, noted that “we hit a bump in the road” when all in-person and public meetings were canceled in late March. But he said the municipality was quick to respond by scheduling virtual hearings throughout April for its land use boards, the redevelopment agency and other entities.

Stakeholders say it was critical to do so for a city that, as of early March, had a development pipeline of more than 30,000 residential units that were approved or proposed for three of its largest neighborhoods: downtown, Journal Square and Bergen-Lafayette. That does not include the city’s burgeoning west side, the home of the Bayfront project and an ongoing, $400 million redevelopment of land owned by New Jersey City University.

The city at the time also had 7,955 residential units under construction across the downtown, Journal Square and Bergen-Lafayette, according to data provided by the mayor’s office.

In an interview, Fulop said it was important to minimize the disruption to development during the public health crisis, in part because of the looming impact on the city’s budget. He noted that, by early March, the municipality was beginning to brace for a $70 million shortfall and taking other steps to minimize the fiscal damage, as it was also moving to close down components of its local economy.

One priority was to make sure the building department continued to function, Fulop said, noting that year-to-date revenue for the agency is actually up from 2019. Doing so “was deliberate as it related to keeping the pipeline moving,” as was quickly moving meetings to online platforms and launching virtual court in early May.

“At the end of the day, New Jersey doesn’t give a lot of flexibility to its municipalities on taxes,” Fulop said. “Your property taxes are the main revenue driver for cities, so you have to keep your ratable base growing. And there really is an opportunity in times like these to continue to drive forward and distinguish yourself versus some of your peers.

“So we tried to make the most of a terrible situation from a city finances standpoint. And it’s worked out OK for us on that front.”

Developers, meantime, have been happy to oblige. For one thing, Jersey City still provides a significant value to Manhattan and even Brooklyn, one that may be even more important in the wake of the pandemic. The city also provides an abundance of newer living options, while still boasting strong connectivity to New York City.

That means builders are no less eager to advance projects that are still months or even years from starting construction.

“We still believe in the apartment market here,” said Jonathan Kushner, president of Kushner Real Estate Group. “Obviously we’ve all taken a pause and this has been a real hit, but we’re bullish on the market long-term and we’re going to continue going as planned.”

Understandably, KRE is forging ahead at sites that were already under construction when the COVID-19 outbreak hit New Jersey. Those include Journal Squared, a project that is helping to revive the mass transit hub and former city center, where the firm expects to deliver 704 apartments next spring as part of its second phase. The developer has also resumed construction at 351 Marin Blvd., the site of a planned 507-unit tower in the downtown, after a six-week shutdown due to the state’s pandemic response.

But Kushner’s firm is also eying future projects, he said, noting that it’s under contract to buy two sites east of Marin Boulevard that could house another roughly 2,000 apartments. And, assuming continued demand at Journal Squared, KRE expects to move forward with a 598-unit third phase.

“The whole world has taken a pause, but we still believe in New York as the financial capital and cultural capital of the world, and people still want to live near it, in my view,” Kushner said.

Other developers have managed to keep their pipelines filled in the Hudson County seat. With bans on large gatherings in effect in late March, the city was among the very first in the state to schedule virtual meetings for its council, planning and zoning boards and redevelopment agency, among others. Many other municipalities were slow to do so, and those that did act quickly have often been hesitant to tackle big projects during the stay-at-home order.

The decision has allowed major projects to move forward in Jersey City, including a high-profile arts and residential development on New Jersey City University’s west campus. The project —which will include a performing arts center, 343 apartments and retail and restaurant space — received approval at the city’s first virtual planning board meeting on April 28.

The ability to keep the pipeline moving has major implications for financing projects.

“Every week that goes by that they don’t have that approval is delaying their ability to get funding,” said Joseph Mele, the director of civil engineering for Dresdner Robin, whose Jersey City-based firm is part of the performing arts center project team. He noted that other regulatory bodies, including the state Department of Environmental Protection, have also been responsive in advancing projects during the emergency period.

Other existing projects have moved forward in the city, Mele said, although there was a brief slowdown in “new opportunities” that had not yet started the entitlement phase. By early to mid-May, however, those projects were also beginning to pick up.

“Clients that were in the very initial planning phases seem to be going back to them, resurrecting and moving them forward now,” Mele said in an interview in mid-May.

Still, not every development is moving full steam ahead. Fulop noted that, while Jersey City has a robust pipeline of hotel projects, some of those developers have stumbled after the hospitality sector was decimated by the coronavirus pandemic.

“We have some of the hotels that were moving forward prior to the pandemic tell us that they were having difficulty financing those projects,” he said. “So we’ve been working with them on repositioning the projects, maybe to more residential, scaling back the number of rooms, but we’ve tried to remain flexible.

For instance, he pointed to a project in the city’s Journal Square section, where a developer’s plan included both residential and hotel components. With the current headwinds in hospitality, City Hall is keeping an open mind “in order to make sure that the project works long-term.”

“With that sort of thing, I think you have to be understanding because it’s certainly beyond their control,” Fulop said. “So we have seen some of those, but what we try to do is adjust the projects to a way that it works financially and they can finance it.”

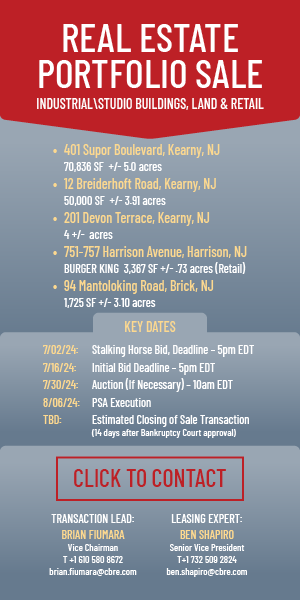

Jersey City names development team to launch 100-acre, mixed-income Bayfront project