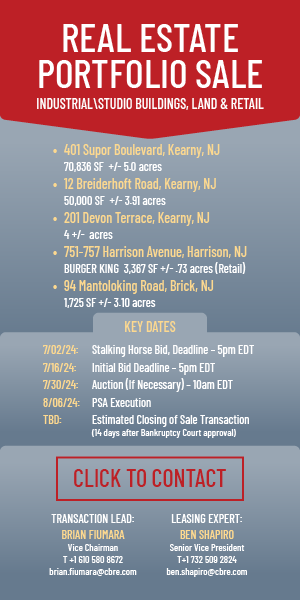

Executives with Rockefeller Group say the addition of in-house design and construction professionals has helped shave three to four months from its development process. Pictured here is the firm’s recently completed, 400,000-square-foot distribution center at 65 Baekeland Ave. in Middlesex Borough. — Courtesy: Rockefeller Group

By Joshua Burd

In a time when industrial builders can’t deliver new space fast enough, those with in-house design and construction teams are finding ways to speed up the development process.

The Rockefeller Group has honed that strategy in recent years with a series of key hires in the region. In the process, executives say the moves have also provided a leg up in the increasingly competitive and increasingly complex search for new sites.

“The type of person that we’ve hired is paramount,” said Mark Shearer, a senior vice president and regional development officer for Rockefeller Group’s New Jersey and Pennsylvania region. To that end, the firm has bolstered its team in the last three to four years with several experts in engineering, project management, underwriting and other disciplines.

Michael Leondi, the company’s vice president of design and construction in the region, cited common issues with industrial parcels such as geotechnical and environmental concerns. With a civil engineer on staff, a developer can “get most of those big questions answered” in a matter of days rather than weeks.

That translates to expedited due diligence and fewer qualifications as the company prepares to negotiate on the property and, ultimately, faster delivery.

“We can go into it from a much more informed position,” said Leondi, who is based in Rockefeller’s Morristown office. “And I think that’s starting to give us a real big advantage.”

Both he and Shearer were quick to note that “the goal is not to replace the outside professionals,” but refine the firm’s strategy at the front end.

“It allows us to establish our risk profile a lot more accurately, much more quickly — instead of 150 to 180 days of just trying to get our feet on the ground and figuring out how the project approach should look,” Leondi said. “That’s shaved down to really 30 or 45 days. And then as the consultants come on board, we utilize their experience and expertise to bolster these assumptions, but we’re finding that we’re getting a lot more accurate coming out of the shoot with it.”

Shearer believes that approach has helped his team cut three to four months from its delivery time for projects in the region, he said, such as a recently completed, 400,000-square-foot distribution center in Middlesex Borough, along with a neighboring 2.1 million-square-foot logistics park in Piscataway that it completed in 2019. And he expects that pace to only accelerate.

That’s likely welcome news for a market that remains vastly undersupplied and highly sought after by tenants, with industrial vacancy in the state falling to 2.5 percent at midyear, according to JLL. The real estate services firm found that New Jersey recorded 12.3 million square feet of leasing activity in the second quarter, the third-highest total in history, fueled largely by e-commerce players and third-party logistics firms.

JLL also noted that Class A buildings accounted for more than 55 percent of that activity, highlighting the importance of new construction for warehouse and distribution center users. That has caused rents to spike alongside the price of land, which Rockefeller said now accounts for at least 50 percent of development costs, up from 20 to 30 percent five years ago.

The upside is that industrial developers are now comfortable taking on more challenging sites that, in past years, would have been off limits.

“The increase in land prices and the increase in profitability in a lot of the projects has allowed more complex sites to get put into production,” Shearer said, “because it wasn’t that long ago that the cost to clean up the site would have been worth much more than you would have ever gotten paid for it.”

He said that having greater certainty on the front end, thanks to Rockefeller’s growing in-house team, allows the firm to navigate a seller’s market for land.

“We can be a little more aggressive with the tighter underwriting,” Shearer said. “If we have more certainty, we’ll do fine. If we have three pages of loose ends, I am not real comfortable pushing that land value to the max.”

That expertise can also help a developer win the trust of a seller who is inundated with offers, many of which may be from less experienced buyers, Leondi said. What’s more, it has allowed Rockefeller to be more selective and find off-market opportunities to acquire its next development parcel.

When it comes to securing government approvals for its projects, Shearer said it was equally important to “have professionals that speak that language.” That can also help facilitate the start of construction, in a state where tenants had preleased more than 52 percent of the 14.1 million square feet of the industrial space under construction at midyear, according to JLL.

“We don’t have to go through an education process to get entitlements done,” he said. “We know what the next step is going to be and we can proactively map that out at the beginning of a project.

“I think having seasoned professionals allows that to happen … and generally when we go for entitlements, what we propose are things that we have a very high degree of certainty will get approved.”