Matrix Development Group has lined up approvals for a 5.5-acre parcel along the Passaic River that could support up to 2 million square feet of office space. Plans for the site were included as part of Newark’s state-supported submission for the Amazon HQ2 project. — Courtesy: Matrix Development Group

By Joshua Burd

These days, it’s not uncommon to see crowds of well-wishers and stakeholders filling the room for a high-profile announcement or the celebration of a major milestone in Newark.

In mid-October, when the state announced its support for the city’s bid for a second Amazon headquarters, that crowd included the owners of many of Newark’s largest or most viable development sites. Those firms are often competing for the same tenants, but the quest for Amazon prompted an unprecedented level of cooperation among landlords and city officials who managed to see the bigger picture.

Joe Taylor, CEO and president of Matrix Development Group, said the stakes couldn’t have been any higher.

“We agreed that the way to approach this thing was to treat it as if it was an Olympic city bid,” Taylor said, rather than focusing on individual sites owned by opposing landlords.

“All of our sites would have to be included on one basis or another in order to properly accommodate what Amazon wants, and (we agreed) that we should all get together and work on it without worrying what comes to any one of us, knowing that all of us will get a piece of it. “And even if we didn’t, we’d all be better off because the ancillary demand that goes with an HQ2 would be very dramatic, whether it’s residential, whether it’s companies that want to be nearby and collocate.”

While there are still months to go before Amazon reveals it selection, making the pitch has rallied developers and public-sector leaders in a way that Newark hasn’t seen in recent memory. That show of unity was only amplified on Oct. 16, when Gov. Chris Christie announced that the state would officially support the city’s bid, even as several other cities in New Jersey jockeyed for the project.

That support includes a $5 billion incentive package — seemingly with bipartisan support — for a requirement that could go as high as 8 million square feet and ultimately produce 50,000 new jobs. The municipality has pledged a property tax abatement that could be worth another $1 billion and said it would waive its payroll tax for the e-commerce giant.

Insiders see it as the ultimate stamp of approval for a city that has completed or broken ground on a long list of large developments in recent years, which have also stemmed from public-private cooperation. Several of the developers behind those projects are among those whose sites are incorporated in the state’s official submission, including Fidelco Realty Group, Lotus Equities and Edison Properties.

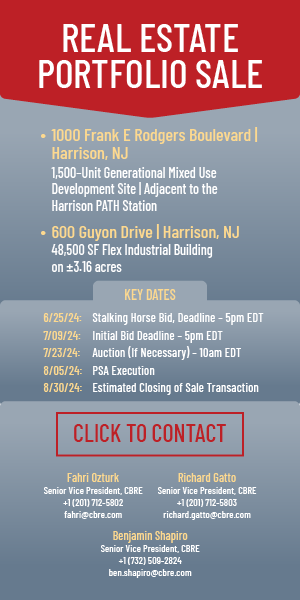

For its part, Matrix owns 5.5 acres along the Passaic River that Taylor said could support up to 2 million square feet of office space. The parcel, which is alongside the Newark Legal Center and the four-year-old North American headquarters for Panasonic, was included in the city’s proposal and could “break ground very quickly and participate in the earliest phases of the Amazon HQ2 requirement.”

The site is also directly adjacent to Newark Penn Station and McCarter Highway, allowing it to tap into the robust transportation network that city and state officials highlighted in their bid. They also touted the region’s large population, its access to talent and education, unique cultural offerings and a vast web of underground fiber optic cable that can produce the fastest internet in the country at affordable prices, they said.

It’s why so many other business leaders see Newark’s chance to compete with the dozens of cities and regions nationwide that responded to Amazon’s request for proposals. And displaying a united front could play an important role: Jay Biggins, a Princeton-based site selection consultant, said offering the certainty and the ability to handle such a large requirement can be especially attractive.

By comparison, a city that is touting a deep technology labor pool may not have such an advantage “because it’s not about what’s there today,” said Biggins, executive managing director of Biggins Lacy Shapiro & Co. Arguably, that level of talent is actually irrelevant, given that “this project will be of such scale that it will attract talent to wherever it goes.”

“It is a destination employer, so the more relevant considerations are really more in the nature of a city planning presentation, because it’s really a challenge as to how any locality will be able to accommodate 50,000 additional workers in the same location” and account for the impact on housing, mass transit and other variables, he said. “So in that sense it’s really more of a mixed-use development, conceptual plan with commitments to the approvals and the funding levels necessary to make sure that the infrastructure will be there.

“I think site assemblage also is an interesting challenge in terms of what levels of certainty or reliability can be provided as to the ability to deliver 8 million square feet, when dealing with locations where all of the land required is not already under common control.”

To that end, Biggins also said the submission was akin to an Olympic bid.

Aisha Glover, who spearheaded Newark’s effort in assembling the submission, said the “phenomenal outpouring” from developers and other stakeholders was a key part of a presentation to state officials. The list of landlords included some that don’t even have property in the city, she said, noting that they and other firms volunteered time and services for the bid.

“Many of them supported us with actual letters of support making commitments to Amazon,” said Glover, CEO and president of the Newark Community Economic Development Corp. “Many of them, even if we weren’t using their site, see the benefit of having an Amazon in the city, so you can just consider that as every developer in the city is supporting in some way — whether physically or mentally — dedicating staff time, energy, resources.

“And some of them have sites that are within the portfolio and some don’t.”

Not that Newark is unaccustomed to seeing collaboration. Many of the city’s recent economic development success stories — such as Teachers Village and the rehabilitation of the historic Hahne & Co. building — have resulted from complex financing formulas with a medley of public and private funding sources.

The city has been able to bring together different stakeholders around many of those projects in recent years and now seems to have a clearer path toward a long-awaited revitalization. Taylor believes joining forces for the Amazon bid was the culmination of that momentum.

“I think it’s a recognition by everyone that if we all pull together, it will help move the market faster,” Taylor said. “A lot of what you see out there is really strong individual efforts, and it’s about bonding together.

“Every successful city, I think, ultimately gets to this place for development or redevelopment, where there’s a sense that the greater good is going to help everyone — and Newark is now there.”