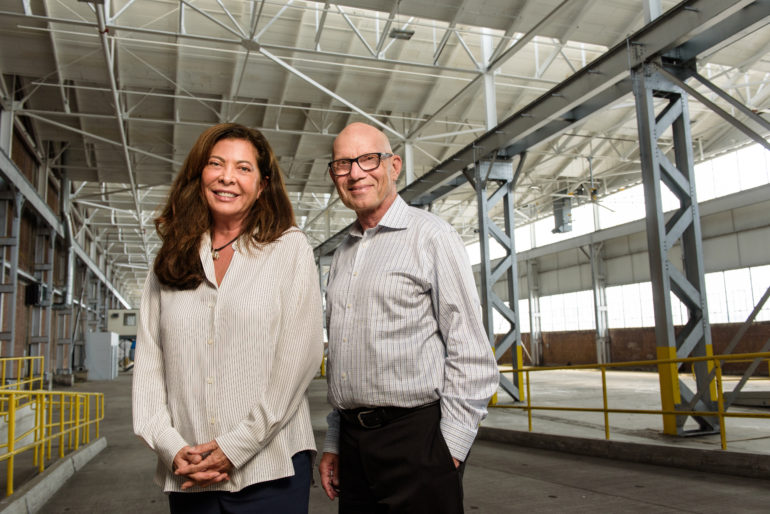

Hugo Neu Corp. Chairman and CEO Wendy Neu (left) and Steve Nislick, the firm’s chief financial officer, lead the team overseeing the redevelopment of the historic former shipyard now known as Kearny Point. — All photos by Jeffrey Vock for Real Estate NJ

By Joshua Burd

The gritty industrial backdrop of highways, warehouses and truck traffic has obscured the historical significance of the South Kearny peninsula, the former home of the Federal Shipbuilding and Drydock Co. through the first and second World Wars.

At its peak in the 1940s, the complex was a city within a city, employing some 30,000 workers as it churned out destroyers, frigates and other ships for the U.S. naval effort abroad.

Those days are long gone, but the current owner of the 130-acre site is hoping to honor its legacy by ushering in a new era of economic prosperity.

The owner, Hugo Neu Corp., is redeveloping the complex as a hub of flexible office space for startups, creative businesses and others seeking a modern workplace. It aims to do so while taking advantage of the historic, architecturally distinct buildings on the site, some of which offer the type of soaring ceilings and open-air feel that appeals to edgier tenants.

“There’s millions of square feet in Brooklyn and now Manhattan, but I don’t think New Jersey developers necessarily feel there’s a demand from New Jersey tenants for this space,” said Steve Nislick, chief financial officer at Hugo Neu. “I can tell you there is, and I think New Jersey has its own creative engine and they’re looking for a place to go. Hopefully, we’re that place.”

These days, the firm can feel more confident than ever about its ambitious plan.

Hugo Neu has converted a 207,000-square-foot warehouse on the site into loft-style, flex office space with polished concrete floors and 13-foot-high ceilings. Known as Building 78, the space is just about fully leased and now home to more than 100 tenants, from craft-food artisans and a vertical farm to filmmakers and contractors.

RELATED: At Kearny Point, diversification is key

It’s one of six buildings that would be repurposed under the plan by Hugo Neu, a privately held, 70-year-old firm that grew to become a titan of the recycling and scrap metal business. And it’s an early source of momentum for the roughly 2 million-square-foot project, which could equate to a $1 billion investment over the course of a decade.

Next up is a new 200,000-square-foot light industrial building — now under construction — that will be marketed toward small-scale manufacturers, food processors and other businesses with storage requirements. The firm is also set to begin the adaptive reuse of an adjacent structure to create 250,000 square feet of office space for larger users.

“We really wanted to create activity here and real economic development for this region,” said Wendy Neu, the firm’s chairman and CEO. “With 130 acres, we think we have a large enough footprint that we can really make a difference.”

All that comes with a set of public policy goals that Neu and her team have heeded since they began to craft the plan about three years ago. Chief among them is to create about 7,000 new jobs, they say, with a focus on diversity and providing a home for New Jersey’s creative class. Already, about 60 percent of the firms in Building 78 are woman- or minority-owned.

The developer is also focused on the sustainability of the property, which sits at the confluence of the Hackensack and Passaic rivers.

“After Sandy, this site was under four feet of water, so obviously we have to protect against future flooding events,” said Michael Meyer, Hugo Neu’s director of development. “So we’ll be incorporating lots of green infrastructure and green technology into the redevelopment of the project.”

That includes new open space along the shoreline to help restore the natural ecology of the peninsula. The developer is also raising the floor of each building that will be left standing.

Trying to achieve those goals is one reason for not pursuing a more traditional use at Kearny Point. The complex sits among the industrial neighborhoods that surround the truck portion of Route 1&9 between Newark and Jersey City, with quick access to the New Jersey Turnpike and Port Newark-Elizabeth.

Even Nislick conceded that “99 percent of the developers, particularly New Jersey-oriented developers, would demolish all of these buildings and just build high-bay industrial buildings.” And that was an option at one point as the firm considered what to do after Sandy.

Neu said that “when Steve joined us is when we started rethinking the site,” noting that development was never a core business for Hugo Neu. The firm had acquired the property in the early 1960s for the purpose of dismantling ships and would go on to rent the buildings to industrial users.

But it was in limbo as a landlord after the massive flooding event.

“Sandy was when we had to think about, ‘Are we going to save the site or just leave it as is?’ ” Neu recalled. “We could have left it the way it was because, essentially, none of our tenants left, which was rather surprising, but we knew that we had to make a decision at some point.

“So Steve had other ideas and I was into doing something very different. We developed a team around that and this is where we are today.”

Hugo Neu’s vision for Kearny point may seem like a far cry from its days as a hub for shipbuilding. Federal Shipbuilding, a subsidiary of United States Steel, was launching a ship just about every five days from the site during World War II, a credit to the high-intensity and state-of-the-art operations taking place at the complex.

But Nislick saw the grittiness and the industrial feel of the buildings as the perfect fit for creative flex space. For instance, he said Building 78 “lays out perfectly for what we built here,” with its 40,000-square-foot floor plates and the ability to capture light and air.

And from a land use and density standpoint, industrial space would be significantly less efficient, he said, noting that truck parking would take up more than half of the footprint of such a building.

“You couldn’t have a better building if you wanted to just lay it out for small tenants, so we started talking” about alternatives to warehouse and distribution space, Nislick said. “Here you have a 200,000-square-foot building and you’d end up with a 40,000-square-foot industrial building.”

As the former CEO of Edison Properties, Nislick helped lead a company whose portfolio included flexible office space, so he was confident that “there’s always a huge, huge demand for quality, well-serviced space prebuilt for small tenants.” But he said most landlords aren’t interested in short-term leases or in catering to small tenants with prewired spaces.

Once he and his team came to believe that South Kearny would provide the right location for meeting that demand, they moved ahead with Building 78 and the overall master plan, tapping WXY and Studio Architecture for the project. The first tenant committed in late 2015, and the response that followed has indeed been encouraging.

Tenants at the space have ranged from single-office users taking as little as 30 square feet to businesses requiring 10,000 square feet, Nislick said. Rents have averaged around $18 per square foot, and Hugo Neu has been willing to offer month-to-month and flexible terms as a means to establishing a foundation of small users at Kearny Point.

Already, about 15 tenants have expanded in the space.

“It’s a long-term program,” Nislick said. “We’re looking to create both a community and the feeling that tenants feel like they’re not just tenants. We’re not a landlord looking to maximize rents — we’re looking to really maximize the value of the community.”

In March, Hugo Neu announced that it had partnered with Uber, offering a $50 credit to select tenants as a way to increase accessibility to the site. Kearny Mayor Alberto Santos believes that offering helped Kearny Point overcome one of its main challenges, he said, noting that the nearest mass transit is at the Journal Square transportation hub in Jersey City.

“That kind of raw space is hard to find at affordable rents in the New York City area,” Santos said, “so I think they were able to overcome the mass transit concern by offering affordable rents and trying to address access to and from Journal Square (through the Uber partnership).”

Hugo Neu hopes that foundation will support its other plans for the site. Along with the new light industrial building that is now under construction, the firm is targeting larger office users in its next retrofit at the complex. That space will occupy Building 100, a cavernous structure that sits near the southern shore of the peninsula and offers views of the Manhattan skyline.

As for how it plans to finance the massive undertaking, the firm only said it would use public and private funding. The developer received a long-term payment in lieu of taxes agreement from the town for Building 78, and Santos believes that will continue to be the case in the next few phases.

Hugo Neu also will likely tout the availability of state incentives for tenants considering Building 100 and Building 54, a separate structure that could support as much as 500,000 square feet of office space, Nislick said. The latter, a building that once housed the cranes used to assemble the ships at the complex, will likely be the largest on the site, offering a 62-foot clear height and a 100,000-square-foot mezzanine level.

Members of the development team acknowledge that their plan is also contingent on creating open space and amenities. That would entail eventually razing many of the buildings that line the western shore of the property and are still leased to traditional industrial tenants, with a total footprint of around 1 million square feet.

While Hugo Neu is still determining which ones will come down, its plan is to replace them with smaller buildings farther away from waterfront and create an active shoreline. The firm is also planning to redevelop a 20,000-square-foot former power plant building as an amenity and retail center, all meant to help create a sense of place for the complex.

“We’re really doing a lot of the amenity planning now and making sure there’s an adequate array of services in addition to the open space,” Meyer said. “That will create the kind of community that we know that these creative office users want to find.”