Plans for Boraie Development’s latest project in New Brunswick call for a 342-unit luxury apartment tower at 11 Spring St., where it would redevelop what is currently a parking garage within its Albany Street complex. — Rendering by MHS Architecture/Courtesy: Boraie Development

By Joshua Burd

Developers are laying the groundwork for what could be a new wave of apartment construction in downtown New Brunswick, seeking to meet the needs of potentially thousands of new employees that will come from several transformative, large-scale commercial projects that are now taking shape.

That’s evident from several residential buildings that are slated to break ground this year and from a growing pipeline of land use applications. Officials say that, from 2022 through 2024, the city approved projects with a combined 2,071 housing units — nearly double the number of apartments constructed from 2015 to 2023 — while there were another 824 units in various stages of entitlements as of late February.

According to local officials and property owners, the growing interest from residential builders has translated to a flurry of land use applications over the last three years. The city approved projects with a combined 2,071 housing units from 2022 through 2024, according to its planning department, while there were another 824 units in various stages of entitlements as of late February.

Several of those developments are slated to break ground in 2025.

“There’s a perceived demand — and I think it’s a real demand — particularly as a lot of younger people are coming into the city to work,” said Chris Paladino, president of New Brunswick Development Corp., or Devco. The not-for-profit developer is behind the two largest commercial projects under construction in the downtown — the 12-story, 520,000-square-foot Jack and Sheryl Morris Cancer Center at Somerset and Division streets and the 574,000-square-foot first phase of the Health + Life Science Exchange or HELIX campus, which will house Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, a facility for elite researchers from Rutgers University and a 55,000-square-foot incubator — both of which are expected to come online this year with a combined value exceeding $1.5 billion.

This year is also slated to bring the start of construction for Nokia Bell Labs’ new 360,000-square-foot lab and office tower, which will be built by SJP Properties under the HELIX’s second phase, in a project that would bring 1,000 scientists, engineers and other talent to the city by 2028.

“These are the top people in the country,” said Robert Weiss, president of New Brunswick-based Weiss Properties, referring to the workers that will populate the cancer center and HELIX projects. “And if we want them to live in New Brunswick, which we all do, they expect a beautiful place to live with great lifestyles and great amenities.”

He said the few newer luxury apartment buildings that New Brunswick does have — including Pennrose’s 207-unit Premiere Residences on Livingston Avenue — are virtually full. So are the city’s older rental buildings, but that could change if the development pipeline comes to fruition.

To that end, Weiss Properties has approvals to build a 24-story, 407-unit tower known as The LIV Apartments, designed by Minno & Wasko Architects and Planners, that would rise roughly a quarter-mile from the HELIX. Another firm that has operated in the city for decades, Boraie Development, is planning a new 342-unit project at 11 Spring St. across the street from the science and technology campus, with MHS Architecture leading its design team.

Paladino, meantime, noted that the HELIX’s third phase is currently slated to include 250 apartments over a 240,000-square-foot podium of lab and office space. They’re among the many projects that are in the city’s pipeline, which also includes a planned 22-story, 331-unit tower at Bayard and Kirkpatrick streets by Wick Cos., as well as smaller proposals throughout the city. All of which comes as construction continues on a major project outside the downtown, at the former Sears site on Route 1, where Russo Development is building 531 apartments alongside 168 for-sale townhomes by PulteGroup.

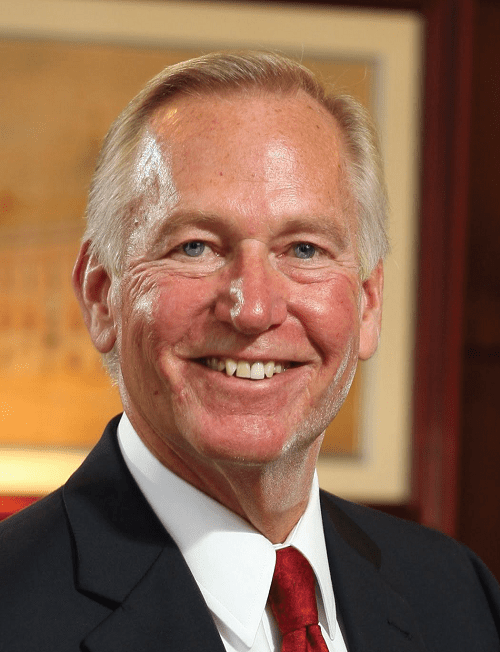

Managing the influx of applications is nothing new for New Brunswick, which has decades of experience and a respected team of professionals that can handle the volume, while ensuring the projects check boxes for design, parking requirements, affordable housing and other factors. Simply put, Mayor James Cahill said, “we sit down, we review them and, if it’s something we like, we facilitate it getting done.”

“Most of the projects that we’re looking at are quality developers who know what they’re doing, have the ability to get site control and understand what our needs are in the city,” he said. “And most of them are pretty easy to work with.

“But we have certain standards we adhere to, and we make sure that people stick to them. The beauty is that … perhaps 30 years ago, we would have been a little bit more lenient with regard to trying to attract people here. But because of the desirability of the city, we can be a lot more selective and definitive about what it is we need in a project for it to go forward.”

Developers have long said that stability in government is one of the city’s key advantages, and that’s no different as a new phase of development emerges.

“New Brunswick, thanks to the longstanding leadership of Mayor Cahill, is entering a new renaissance period,” said Wasseem Boraie, principal of Boraie Development. “The new construction by Rutgers Medical School and Cancer Institute, with Nokia on deck, will add well over 1 million square feet of commercial tenancy to our downtown. Like Monday follows Sunday, the residential development will be there to soak up this new demand.”

The city is well known for its arts and culture, as well as the academic, health care and government institutions that have anchored its economy for decades. But Weiss, who also cited Cahill’s role in revitalizing the city, said the billions of dollars in new investment “is what led us to really get going on The LIV as a complement to this surge, because we’re a piece of this puzzle.” And the expected influx of high-income professionals who can afford luxury apartments will help developers justify the cost of high-rise steel and concrete construction, Weiss said, which has often been elusive in the past.

“You can build this all day long, but you need the rents to support it,” he said, later adding: “We know the market is there. This market is coming, and this is not a projection, because when we want to know when, we just have to walk out to the HELIX and see how far along they are.”

The need for those projects is increasingly clear. Paladino noted that Rutgers is actively recruiting principal investigators for what will become the translational research facility at the HELIX, each of which figures to have a team of six to 10 people, meaning the arrival of potentially hundreds of new occupants by the time the facility is fully staffed.

Nokia, for its part, “was very in tune with housing that was available and housing that was planned.”

“Over the next seven years, about half of the workforce of Nokia is retiring, and they’ll be hiring young engineers and mathematicians and physicists, which they believe will want to live in the city,” Paladino said. “So those are the conversations we have.”

Notably, the city’s development pipeline includes hundreds of new affordable housing units, either from standalone projects or as a percentage of the larger projects, that will add to the existing stock of roughly 1,500 homes for low- to moderate-income renters. That’s critical, Cahill said, given the broad workforces that the new projects will employ.

“We’re under no obligation from the state to continue to build affordable housing, unlike a lot of our neighboring municipalities, but we still push that,” Cahill said. “We still find, because of New Brunswick and its diversity, that affordable is what we need to do, because we’re diverse in so many ways, and one way we’re diverse is income levels.”

The mayor and other stakeholders point to the importance of a nearly $50 million upgrade of the New Brunswick train station, which he said will address long-overdue repairs while modernizing parts of the facility. The city is pushing for funding for additional renovations, Cahill added, so that “we will have a train station that will mirror all that’s going on” in the surrounding blocks.

In the meantime, local officials are taking a holistic approach to support the new development on the horizon. Supporting and adding to New Brunswick’s acclaimed arts and cultural scene is “one area that we always have to be focused on, looking for opportunities to grow,” Cahill said. The city is also in the midst of a sweeping plan to update or replace many of its 17 parks in the years to come, while construction is underway on a new one-acre park at a former parking deck property on Neilson Street.

Beyond that, Cahill said the municipality is spending $87 million on water utility improvements — to increase output while replacing water lines and treatment facilities — as part of a broader, ongoing effort to address its infrastructure.

“A lot of municipalities don’t worry about those things,” Cahill said. “It’s underground, nobody sees it, but it becomes noticeable when it’s a problem. We are trying to stay ahead of the curve and are not afraid to spend money to save money down the road.”