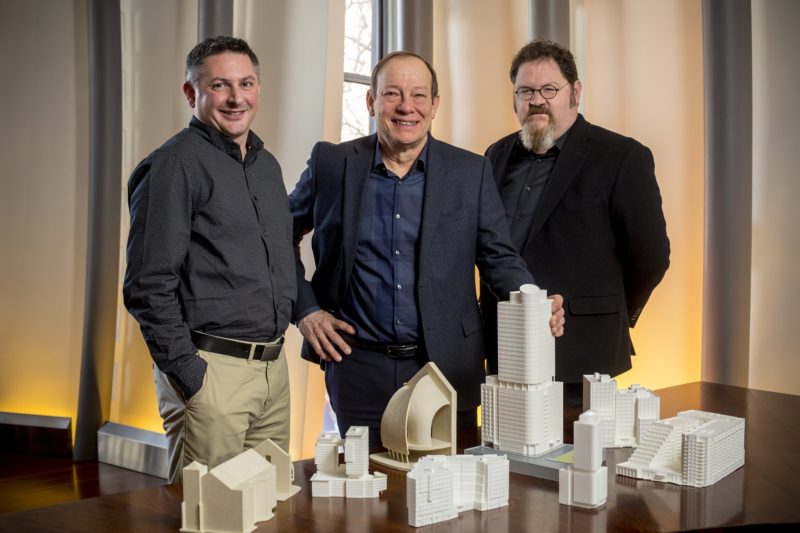

Dean Marchetto (center), the founding principal of Marchetto Higgins Stieve Architects, launched his design firm in 1981 as Hoboken was on the verge of its multifamily boom. He is joined by fellow principals Mike Buldo and Bruce Stieve, who lead the firm along with Michael Higgins. — Photo by Aaron Houston for Real Estate NJ

By Joshua Burd

Dean Marchetto could certainly make the case that timing is everything.

Just a few years into his career, the 26-year-old architect became connected with aspiring Hoboken developers Daniel Gans and George Vallone, who offered a project that allowed him to leave his job at a high-end, Manhattan design firm and start his own practice in New Jersey. It was the early 1980s — on the precipice of Hoboken’s multifamily boom — and it wasn’t long before Marchetto would reap the benefits of being on the front lines.

Along with projects from Gans and Vallone, Marchetto would also find an opportunity with another up-and-coming developer, Sandy Weiss.

“Here I am, a young architect starting my business, and in a matter of a year I’ve got 250 units that I’m building,” said Marchetto, the founding principal of what is now Marchetto Higgins Stieve Architects. “I said, ‘Something’s happening here,’ and I was in the right place at the right time.”

The practice has been based in Hoboken ever since, having designed more than 100 projects in the revitalized Mile Square City. But it has also grown over nearly 40 years by expanding outward from its original location. Most recently, the firm has amassed a pipeline of suburban but transit-oriented residential projects to the west of Hudson County, bringing it to well-known locales such as Morristown, Montclair and Westfield.

Such projects — which span more than a dozen buildings and 1,800 units built outside Hudson County — have been critical to MHS, as they have been to developers that have sought new markets and local officials that have sought to revitalize their downtowns. And Marchetto sees continued opportunity in not only those communities, but in lesser-known suburban downtowns.

“With the whole idea of smart growth and transit-oriented development, people were starting to get the message that these downtowns are the place to grow,” Marchetto said.

Marchetto, who grew up in nearby North Bergen, began his career in the late 1970s at Gwathmey Siegal & Associates Architects in Manhattan, where his work included designing high-end homes in the Hamptons. He spent his nights doing freelance design work in New Jersey, and it was around 1981 that his cousin, a former high school classmate of Gans, introduced him to the young developer, paving the way for Gans and Vallone to hire him to design an apartment building at 151 2nd St. in Hoboken.

When the city’s zoning board approved the 25-unit project, Gans asked Marchetto to continue on with the construction drawings. The young architect realized that would require far more attention than he could provide as a part-time freelancer.

“I’m scratching my head saying, ‘I’m not going to be able to do this at night in my spare time, because it’s a fair amount of work,” Marchetto said, so he came up with a price that would allow him to leave Gwathmey Siegal and start his own firm for at least six months.

Working out of a converted ground-floor apartment in Hoboken, Marchetto took on additional projects for Gans and Vallone’s Hoboken Brownstone Co. and then for Weiss, who hired him to design a 104-unit high-rise on Observer Highway known as the Skyline. The firm focused solely on Hoboken throughout the 1980s, bringing on additional architects and moving into a larger space on Washington Street, before the market came to a halt at the end of the decade.

While Marchetto had pivoted to public-sector clients such as schools and housing authorities, the return of development in the mid-1990s allowed the practice to refill its pipeline. And it was around that time that Michael Higgins and Bruce Stieve, the firm’s other two namesakes, became partners in the business. In a time when young architects would often establish themselves and then go out on their own, Marchetto realized that “these are guys that really have great talents that I could see myself working with for a long time.”

Together, the trio continued the firm’s focus in Hoboken while expanding to neighboring communities such as Jersey City, Union City and Weehawken, building a larger footprint in Hudson County that remains strong today.

Still, with the onset of the 2008 downturn, the firm pulled back a second time and bided its time with public-sector work, Marchetto said. But by around 2011, the multifamily construction industry was beginning to churn once again. This time it was spreading westward to suburban communities with train stations and surface parking lots, where local leaders were searching for ways to generate new tax revenue in order to support their own rising costs.

With the slowdown of the single-family housing market, officials became open to the idea of midrise, mixed-use development around mass transit, which would also help bring new foot traffic to a town’s central business district.

“(They realized) there’s room to grow in the downtown and it’s appropriate for it to grow,” Marchetto said. “It enriches the downtown environment and provides opportunities for folks who need apartments, as opposed to homes, and it’s changing the dynamic.”

Fittingly, one of MHS’ first projects outside Hudson County was in Morristown — widely hailed as a model for downtown revitalization — where it was tapped by Mill Creek Residential for the 248-unit complex known as Modera 44. The firm has since added several projects to its portfolio in Morristown, including an office building for The Hampshire Cos. that is home to Fox Rothschild LLP, and the 59-unit Metropolitan Lofts on behalf of Woodmont Properties and Roseland Residential Trust.

Landing additional suburban work meant having to face pushback from residents, who typically express concerns about congestion in their downtown and an influx of school children. But Marchetto said that, over time, there is growing evidence that such projects attract young couples and empty-nesters, both of which come with few children.

“I think most people today understand it,” he said. He added that, as young families begin to have children, they often move into the single-family homes that were vacated by empty-nesters, creating a cycle within towns that are embracing downtown redevelopment.

The firm, which has a team of about 36, has also completed designs in towns such as Westfield, Montclair and other well-known communities. Inevitably, one key task is to design a project that can integrate with the surrounding area, which Marchetto said makes it more palatable to governing bodies and local officials.

MHS sought to do exactly that in Madison, where it worked on behalf of Kushner Real Estate Group to design a 100-unit rental project and a 35-unit sister condominium building. Rather than create a closed-off environment, the plans called for creating a public road through the middle of the property with sidewalks, furniture and landscaping that matched the downtown, essentially creating an extension of the surrounding streetscape.

Marchetto also noted that the orange brick design of the complex was inspired by the architecture of one of the borough’s best-known buildings.

“You don’t want to go to Madison and show them a Hoboken-style building,” he said. So each time MHS is hired to work in a new town, it’s commonplace for its team to study the municipality’s existing architecture using photography, drones and other tools.

“We really try to understand the DNA of the historical architecture of the town and then we design a modern building that carries that DNA through to current time,” Marchetto added. “That’s our M.O. And it’s worked for us in a lot of towns because you can’t really go into these suburban towns — the very nice, well-to-do, established towns — and tell them you know better than they do.

“You can’t. You have to go in and work with them and try to come up with an architecture that makes them feel comfortable.”

That approach goes back to Marchetto’s first project in Hoboken, the 25-unit building on 2nd Street, where he sought to blend the larger property with the surrounding single-lot brownstones. That resulted in a façade with a modular, segmented look that had the “contextual rhythm” of the narrower buildings, a choice that is still evident today in many MHS projects.

In many cases, MHS has landed in the western suburbs by following its clients from Hudson County. That’s been true in Montclair, where both Ironstate Development Co. and The Pinnacle Cos. are involved in a mixed-use development at the historic Wellmont Theater. MHS is also working in Montclair on behalf of Bijou Properties, for which it has designed several well-known projects in Hoboken over the past decade.

Marchetto sees additional opportunities in suburbs such as Bloomfield and Berkeley Heights, which also have train stations but are far less heralded. He can only hope the pipeline continues to grow and provide the same benefits, given that the firm’s work in the suburbs has helped it more than triple its headcount since 2009.

MHS also remains extremely active in Hudson County, where its designs have resulted in nearly 8,000 units built. The practice recently opened a second office in the Journal Square section of Jersey City, the onetime epicenter of Hudson County, where Marchetto helped craft a redevelopment vision that ultimately became the neighborhood’s zoning ordinance. The space allows its architects to be in and amongst the projects that are now sparking the area’s revival, Marchetto said, as he did in Hoboken over several decades.

As to the ongoing demand for luxury housing in Hudson County and elsewhere, Marchetto seems as bullish as ever. He feels that way any time he looks across the Hudson River and sees the massive Hudson Yards project in Manhattan taking shape.

“It’s 55,000 jobs coming to the West Side of Manhattan this year. Many of them aren’t going to be living in New York City,” he said, noting that, for instance, a ferry ride from Weehawken and Hoboken can be a faster commute than from many other parts of Manhattan. “And so those jobs right there on the West Side of Manhattan are going to fuel the real estate potential in this area, because they’ve got to live somewhere.”

Among Marchetto Higgins Stieve Architects’ many suburban downtown projects is a mixed-use development at the historic Wellmont Theater, where the firm is working on behalf of longtime clients Ironstate Development Co. and The Pinnacle Cos. — Courtesy: Marchetto Higgins Stieve Architects