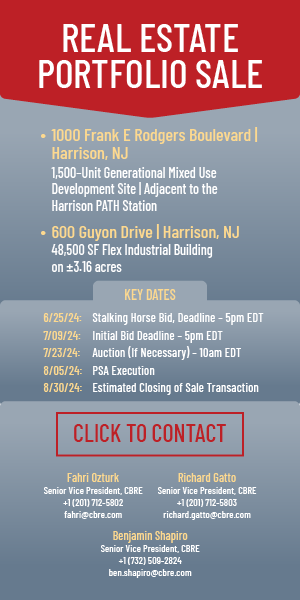

Unilever’s new 325,000-square-foot U.S. headquarters in Englewood Cliffs, developed by what is now EDGE Technologies and Normandy Real Estate Partners, incorporates smart technology and other features in order to make the complex healthier, more sustainable and more energy-efficient. – Courtesy: EDGE Technologies/Normandy

By Joshua Burd

For all the appeal of a modern office building — with a sleek design, natural light and a host of collaboration spaces — sometimes it is what you can’t see that can be even more impactful.

Such as the 15,000 sensors that are placed throughout Unilever’s new 325,000-square-foot campus in Englewood Cliffs, which have revealed that parts of the building were being underused on Wednesday and Friday afternoons. The data has allowed the company to shut down at least 20 percent of the complex at off-peak times, yielding savings on energy, maintenance and other costs.

Call it a glimpse into the office of the future, where smart technology will be increasingly important.

“What smart tech offers us as an industry is only just beginning,” said Jan Hein Lakeman, executive managing director with EDGE Technologies. “As a developer, it’s great because it involves design all the way up to the operation of a building.”

Lakeman, whose firm co-developed Unilever’s new U.S. headquarters, spoke in late September during a program hosted by NAIOP New Jersey. As part of the association’s annual CEO Perspective event, real estate executives offered their take on what they say are the key changes in how office space is designed and how corporations will continue to attract talent.

Amenities, collaboration space and access to transportation will all remain important, they said, but those features must be increasingly focused on wellness, sustainability and energy savings. That’s not to mention diversity and the ability for employees to choose how they work.

For instance, at its campus in Whippany, Barclays offers amenities such as a health center and on-site childcare. But it’s also focused on offering greater flexibility in employee workstations to ensure that the office is “as attractive to the return-to-work mom as it should be for a 23-year-old kid out of the university.”

“That’s about creating choice, it’s about creating a variety of workplace settings, because not everyone wants to sit on a couch and work on a laptop,” said Neil Grassie, Barclays’ global head of capital projects and head of corporate real estate solutions in the Americas. “Some people are distinctly uncomfortable with that.”

He also noted that workers in Whippany do not have assigned desks and that employees outnumber the amount of workstations by around 1,500 to 1,250. Through the use of smart technology and analytics, the company is also able to maximize its space across its footprint and allow its buildings to perform more efficiently.

“We can really sweat this asset, so for us, now on a larger scale, we can take inefficient buildings in a high-cost location like Midtown and build more space, accommodate more people in a far better way and create a healthy environment — and people want to work there,” Grassie said. “You’ve got to create that choice that spans more than just millennials.”

The Barclays executive also noted that developers and corporate tenants are increasingly moving beyond the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED scale, which stands for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, and embracing what’s known as the WELL Building Standard. The latter is “directed more toward user well-being, as opposed to the performance of the building,”

Grassie said, and “with the push to increase density and accommodate more people in less space at a lower cost, it’s essential to provide a healthy environment they want to work in.”

The moderator of the program, Paul Teti of Normandy Real Estate Partners, questioned the panelists as to whether occupiers can embrace building efficiency, sustainability and wellness without incurring major cost increases. Lakeman, whose firm partnered with Normandy in the Unilever project, said the investment was in fact worthwhile: In designing the campus, the consumer products giant agreed to pay about 5 percent more in rent in order to incorporate smart technology and greener, more insulated building materials. The developer, which was known as OVG Real Estate at the time, then pledged that Unilever’s operational costs would go down by 30 percent and its energy bill by 50 percent.

“The old notion that people still have in this industry is that, if you want to make a more sustainable building, then you actually have to pay more,” he said. “This is not the case. … It can be done, as long as you take a holistic approach to doing it.”

Steve Nislick, chief financial officer with Hugo Neu Corp., agreed that landlords have to provide “a generally healthy environment, so that when people leave the building, they feel better than when they walked in in the morning.” The developer is striving to do that at Kearny Point, its 130-acre business and industrial campus in Kearny, where it’s also looking to meet the demand for a more resilient workplace.

Namely, Hugo Neu is demolishing 25 acres of older industrial buildings in order to restore wetlands and create new green space on the site.

“Resiliency as well as carbon footprint are very important to tenants in the 21st century,” Nislick said. “Creating open space not only in the building, but elsewhere on the site is important.

“We think that type of environment will bring huge added value to the site.”

In addition, Hugo Neu has focused on programming and creating a setting “that disparate tenants see as a community,” which is important for a campus that caters to small and midsized users. The firm is achieving that with the right food service, liquor licenses and a willingness to spend money on events.

“Events for this type of space are critical because it creates the community, it allows tenants to meet each other, it allows tenants to do business with each other and it allows outsiders into that community,” Nislick said. “It’s very important when you’re renting small amounts of space to a large number of tenants and when you have a wide diversity of tenants.

“And having a wide diversity of tenants, at least in our mind, is important. People like diversity.”

Focused on flexibility

For Steve Nislick and Hugo Neu Corp., the office of the future may be as much about a landlord’s leasing strategy as it is about building design and amenities.

At Kearny Point, the developer has opted to place a greater emphasis on flexibility, offering leases ranging from 35 to 10,000 square feet. By offering turn-key spaces and the option for short-term leases, Nislick said Hugo Neu is seeking to tap into the demand that WeWork, Convene and other operators of shared office space have captured recently.

That does come with risk, he said, but also opportunity.

“I think that’s where the market is headed, because why would a prospective tenant take a long-term risk when it doesn’t have to, when he doesn’t know where his company is going to be a year from now — whether he’s going to be a growing company or out of business?” Nislick said. “And because wholesalers — and I consider WeWork a wholesaler of space, not an owner of space — is willing to take that risk and landlords aren’t, they’re sort of ceding that space to the WeWorks of the world. Much like the retailers have ceded space to Amazon.”