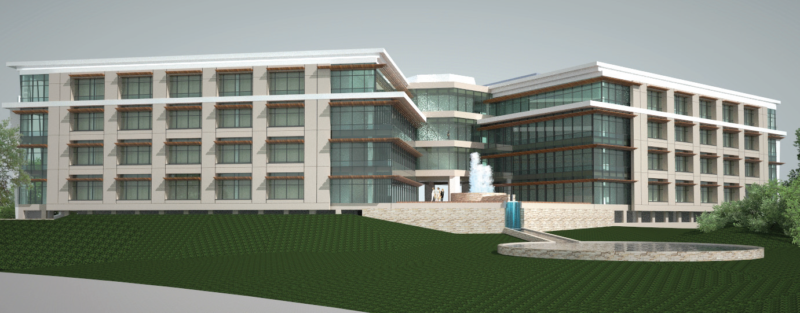

A rendering of the 186,000-square-foot medical arts complex that is slated to come to the former Muhlenberg Regional Medical Center, under a project by CHA Partners. — Courtesy: CHA Partners

By Joshua Burd

Bill Colgan knows the numbers well: When he started his career in health care more than 25 years ago, New Jersey was home to 115 acute care hospitals. Today, there are just under 70.

The opportunity was all too clear by 2008.

“We were realizing that there was really no plan to repurpose these facilities,” said Colgan, a founding member and managing partner of CHA Partners. “And what became apparent is that the inpatient environment was going to continue to consolidate.

“That really became what we saw as the opportunity. It was a changing market, and looking around the landscape, there weren’t many players that were out there addressing that transition.”

CHA Partners has spent the past 10 years doing exactly that, having acquired and repurposed three former hospitals in New Jersey. And it’s now poised to begin its largest project to date — the long-awaited conversion of a shuttered hospital in Plainfield.

The $57 million plan, which was approved by city officials last fall, calls for CHA to develop a 186,000-square-foot medical arts complex and 120 apartments at the former Muhlenberg Regional Medical Center. While CHA’s acquisition of the property is still pending final state approval, Colgan is hopeful that construction could begin as soon as midyear.

Such a milestone would be welcome news to city officials and Plainfield residents, who have been grappling with the void left by the hospital since its closure in 2008.

“Muhlenberg Hospital was an integral part of the Plainfield community for decades,” Mayor Adrian O. Mapp said in early January. “The project that emerged and is now set to begin will not only bring much needed medical services back to our community, it also will provide an important boost to the local economy.”

For CHA, the project will build on a track record that includes repurposing the former Barnert Hospital in Paterson, Greenville Hospital in Jersey City and the William B. Kessler Memorial Hospital in Hammonton. The firm also moved into New York City soon after Hurricane Sandy, building a new medical arts complex in the storm-battered Rockaway section of Queens.

The projects have helped preserve or restore services that disappeared as hospitals closed their doors or filed for bankruptcy, having succumbed to the growing number of empty beds. As Colgan noted, health care spending has continued to rise in the U.S., but many procedures and specialties have moved to lower-cost settings outside the hospital.

“I think one of the drivers is (that) the Department of Health doesn’t have the type of funding it needs in order to make a meaningful impact in the transition from inpatient care to outpatient care,” he said. “So as we watched the disorderly closure of hospitals … how do you capitalize on (the fact that) there’s still a need for health care in the community? And that really was the driving force as to why we focused our efforts on that niche.”

Recognizing that opportunity was decades in the making, dating back to well before the launch of CHA. The firm’s principals include longtime hospital executives and consultants, while Colgan and fellow partner Michael Nudo spent nearly 20 years running the tristate region’s largest health care revenue cycle management firm.

Known as Armanti Financial Services LLC, the business employed more than 600 and had a national client base that included three-quarters of New Jersey’s hospitals. The firm also was an unsecured creditor in several hospital bankruptcy proceedings, all of which gave its principals a firsthand view of the changes in the industry. Colgan and his partners sold the business in 2006, paving the way for the launch of CHA.

Several things became clear since the founding of what was then known as Community Healthcare Associates LLC. Chief among them: The prospects for repurposing a hospital can hinge on when and how quickly the facility is shut down.

“Our preference is always to get in there sooner rather than later, because what happens is that health care services find their way around the community,” Colgan said. “So there are voids that are created and we like, opportunistically, to be able to take advantage when the void gets created, because then we can recruit health care providers back into facilities and we can concentrate them under one roof.”

That was among CHA’s objectives with the former Barnert Hospital in Paterson, a 300,000-square-foot former municipal facility that became its first acquisition. The firm’s effort to convert the property was complicated by a multiyear tax appeal battle with the city, but CHA ultimately prevailed while managing to carry out a $25 million renovation.

Today, the repositioned complex is 97 percent occupied by a host of services, ranging from ambulatory surgical and urgent care centers to dialysis treatment and oncologists.

And while the Plainfield project only received final local approvals last fall, the opportunity dates back to the earliest days of the venture. Colgan said CHA was “just in the midst of starting our game plan to convert Barnert” in 2008 when its principals met with Assemblyman Jerry Green, who was facing the impending closure of Muhlenberg in his home city.

CHA quickly realized that the project was not economically viable on its own.

“He said, ‘What would it take for you to do at Muhlenberg like you’re doing up at Barnert?’ ” Colgan recalled. “And the short answer was, ‘We can’t make the economics work without some sort of incentive program — and no incentive program exists.’ ” The developer worked with Green on legislation for a tax credit incentive program that was ultimately vetoed by Gov. Chris Christie, further delaying the project for several years.

Colgan said CHA became much more involved in 2014, first as a sort of mediator to help advance what had been thorny discussions between city officials and Muhlenberg’s parent, then known as Solaris Health System, over potential redevelopment plans.

When Plainfield requested proposals by early 2015, CHA was among those that responded and presented local officials with a plan to help fill the void left by the acute care facility. The city then started the process of conducting a study and crafting a plan for the site under the state’s redevelopment law, which later allowed it to negotiate a financial agreement with the developer. The redeveloped site is expected to generate some $10 million in benefits to the city in the form of so-called Community Benefit Payments and a payment in lieu of taxes agreement.

CHA’s proposal also went through some changes along the way, including a shift from supportive housing to market-rate apartments and a reduction in the size of the medical component. But Colgan said the finished product was the result of a good faith effort by a long list of stakeholders.

“There was a lot of work on multiple parties’ behalf to ultimately get there,” Colgan said. “The mayor had a really tough battle. The community was not fully supportive, because in their view they should have reopened the hospital. So I give the mayor a lot of credit: He fought an unpopular fight and he realized what the right thing was for the community.

“However, it’s not always politically the right thing to do. So the mayor was willing to take on the challenge of doing the right thing for the community versus the political consequence of doing that.”

With its local approvals in place, CHA now has one final hurdle before it can begin demolition and clear the way for construction. The sale must clear a review under what’s known as the Community Health Care Assets Protection Act, or CHAPA, which considers whether the transaction was open and transparent to ensure that the nonprofit health system received fair value for the facility.

Colgan said the state Attorney General’s Office, which oversees the process, will also be involved in determining what the seller will do with the proceeds. That’s because “the view of the state is that you’ve enjoyed the benefit of not paying property tax, and therefore you’re an asset of the community, so if you sell that asset, you’re obligated to give back to the community.”

It’s just one of the many additional layers of regulation that developers must clear when attempting to reposition a shuttered hospital. Redevelopment in New Jersey is already a complex process that can take several years, but Colgan said introducing health care to the mix can add at least another year to the timeline.

That makes it all the more important that Colgan and his partners have longstanding ties to the state’s health care regulators and hospital systems.

RELATED: $57 million project set to bring apartments, medical complex to hospital site

“We have very deep-rooted relationships in the health care community,” Colgan said. “With that being said, we have a full understanding and knowledge of the licensure process in New Jersey … and what’s required to get drawings through (the Department of Community Affairs).

“We really pride ourselves on being able to compress the timeframe from initial concept to actually opening the facility and to being able to provide a health care service.”

That puts CHA in a position to reposition hospitals and health care facilities as efficiently as anyone else in the industry, Colgan said. He also noted that the firm has a full roster of development professionals, from a partner who is a veteran real estate attorney to a licensed architect on staff and a former longtime municipal government professional.

“Most people don’t understand what makes government tick,” he said. “I think we’ve got a lot of the various moving parts nailed down.”

Those core competencies and the expertise in health care will all come in handy as CHA moves ahead with its newest projects. In Plainfield, Colgan said the 120-unit residential component will take roughly 18 months to complete from the start of construction.

The rehabilitation of the main Muhlenberg building and the creation of the 186,000-square-foot medical arts building will be far more complex. CHA will fit out individual spaces as health care providers sign up, with a mix that could include everything from primary and specialty care to women’s health, a diagnostic laboratory and an ambulatory surgical center.

CHA is prohibited from engaging the site’s current ownership, now part of Hackensack Meridian Health, during the state’s review of the sale. But Colgan was hopeful that JFK Health would have a major presence within the new medical space.

The timeline for the health care complex will also be longer because all of the occupants would be licensed and require Department of Health approval, he said, in addition to reviews by state and city building agencies.

He also noted that the property could have supported a greater concentration of health care had the redevelopment progressed sooner, but that window continued to close as the years passed. It’s why the project is especially fortunate to have a sizable residential component.

“Ten years after the closure of the facility, health care has kind of found its way into the community and other locations,” Colgan said. “So diversity is going to help us here.”

Project diversity

For all of the sweeping changes that have reshaped New Jersey’s hospital landscape, Bill Colgan believes the consolidation of health systems has created a stabilizing force.

That likely means fewer opportunities to convert shuttered hospitals in the way that CHA has done over the past decade. It’s one reason why the firm is filling its pipeline with other projects.

In Totowa, local officials have designated Colgan’s firm as the redeveloper of the sprawling North Jersey Developmental Center campus. The borough has rezoned the 140-acre site to allow for plans that would repurpose around 15 percent of the property, with initial uses including a data center, office space and an assisted living facility, among others.

The 35-building complex, which for decades housed adults with developmental disabilities, was shut down by the state in 2014 as part of a shift toward a more integrated approach to care.

“What we found was that there were a lot of other opportunities that were coming out of the health care space, but they clearly weren’t going to ultimately be health care,” said Colgan, who spent five years early in his career as a developer.

The firm has also completed mixed-use development in its hometown of Bloomfield, including a 476-car parking garage near the Lackawanna Plaza train station. The structure paved the way for new projects near the downtown, including its own 224-unit apartment building and 60,000 square feet of retail.

The developer now has approvals to build another parking structure and an additional 176 apartments, Colgan said.

“We’ve built a lot of good will,” Colgan said. “We invested heavily in acquiring properties and I think we’ve had a very positive experience in working with the government of Bloomfield.”

Rent vs. own

For CHA Partners, developing medical arts complexes has meant being both a landlord and a seller of condominium space within in its projects.

Bill Colgan says that’s due largely to the fact that, at the start of a project, “you would like to believe everybody will be a rental tenant in the building,” yet that quickly becomes an unrealistic expectation. Tenants who are spending hundreds of dollars per square foot on improvements will want to own their space, he said, meaning the developer must be willing to sell the unit in order to maximize its potential to attract different providers.

That has been CHA’s experience over 10 years as it repurposed the former Barnert Hospital in Paterson, where it still owns more than 50 percent of the space but has sold the rest.

“Over time, because of the desire to own and our desire to maintain competitiveness and recruit health care providers into the space, it’s kind of forced us to be flexible with our approach,” Colgan said. “And so we’ve condominiumized some of the space and sold it over time.”