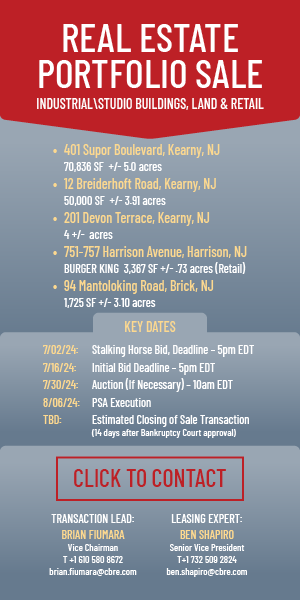

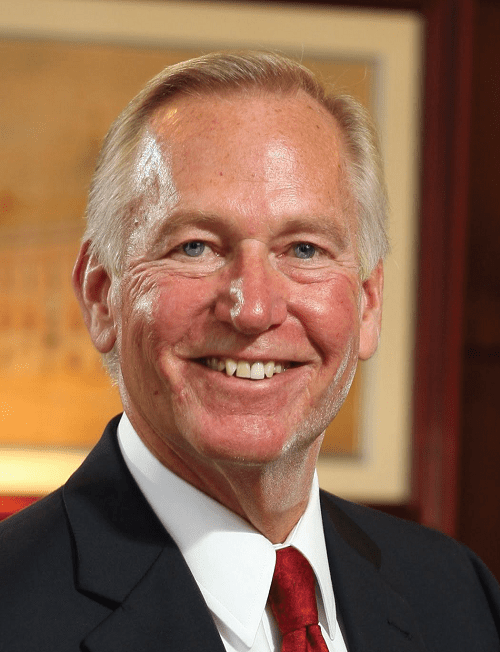

Led by Christopher Paladino, New Brunswick Development Corp. is marking a milestone year after breaking ground on more than $1.5 billion worth of development in 2021. Paladino has led the not-for-profit developer since 1994. — Photo by Hal Brown for Real Estate NJ

By Joshua Burd

For an organization that seemingly thrives on complexity — from vast construction projects to its intricate capital stacks to managing public- and private-sector stakeholders — the success of New Brunswick Development Corp. has hinged on one rather simple objective.

Chris Paladino can’t help but crack a smile at something that sounds so obvious or intuitive.

“Helping public officials fulfill their vision is a very good strategy,” said Paladino, the organization’s president, whose team has developed everything from government office buildings to sweeping campus expansions for Rutgers and Stockton universities.

“It’s helping them get to where they want to go and using skills and resources that we have, because they’re aligned with what we’re trying to do,” he added. “We’re trying to create jobs and redevelop and make New Jersey’s cities a better place to be.”

Straightforward as it may sound, there is nothing easy about what New Brunswick Development Corp. has done for the past three decades, during which it has completed 8.3 million square feet of development with a combined $3.5 billion in investment. The not-for-profit organization, better known as Devco, is also unlike any other developer in New Jersey with respect to how it functions and the scale at which it operates.

All the more notable: It has never done the same project twice, despite having a formula that it has repeated and refined from one high-profile development to the next.

“Devco does not work on cookie-cutter transactions — but it’s really by design,” said Anthony Coscia, a partner with Windels Marx and the developer’s longtime counsel. He points to the “enormous amount of effort” that’s required to bring together an array of public- and private-sector interests and funding sources, as Devco does, in a way that is not feasible for conventional builders.

“So a nonprofit developer like Devco will take a project that does require a whole lot of predevelopment work — that could sometimes be measured in years — in order to bring a project together, because its economic structure is really geared toward the successful completion of the project, not return on capital,” Coscia said.

The power of that strategy was on full display in 2021, a year in which Devco broke ground on more than $1.5 billion worth of development — including the state’s first freestanding cancer hospital and a 560,000-square-foot research and innovation campus, both in downtown New Brunswick. The milestones also came less than three years removed from two other transformative projects: a mixed-use, $172 million performing arts complex in the city and the $210 million Gateway project, which brought a new satellite college campus and a corporate headquarters to Atlantic City.

“In a city, in general, you need to create critical mass,” said Paladino, a New Brunswick native and Rutgers alumnus, who joined Devco as its president in 1994 after serving as the deputy director of the state Economic Development Authority. That meant he was able to draw on his experience in state government in support of his new role, doing so alongside Coscia, the former EDA executive director, and George Zoffinger, the business magnate and former authority chairman, who had stepped in to lead Devco’s board.

“We saw too many cities make the mistake of doing a project here and then doing one eight blocks away. They should do them across the street from each other.”

That experience, along with Paladino’s ability to connect with political, business and institutional leaders, has been integral to Devco’s success. Their support is a common thread in each of its projects, he said, noting that they are in turn counting on the developer to “help meet public policy goals that are going unfulfilled, either by the public or the private sector.”

Typically, the projects also involve an eclectic layering of funding and financing sources from government, the capital markets and everything in between — from third-party equity to parking authority bonds to high-profile state tax credit programs.

“There are things that the government is not set up to do and there are risks that the private sector doesn’t want to take,” Paladino said. “So we kind of stand in that abyss between those two things.”

The New Brunswick Performing Arts Center, which opened in 2019, “is a perfect example” of that process, he said. The $172 million project was nearly a decade in the making, stemming from a desire by Mayor Jim Cahill and others to double down on an industry that draws 300,000 patrons to the city annually. For many, that meant updating the aging, scattered facilities for the three active theater organizations in New Brunswick, which could only boost the economic impact on restaurants, hotels, parking and the residential market.

By the time it broke ground in fall 2017, with Devco at the helm, the project had attracted nearly 20 other stakeholders beyond the initial theater groups, from the city, county and state agencies to Rutgers’ Mason Gross School of the Arts. Paladino also noted that Pennrose, a private developer, would buy the air rights to build 207 apartments above the state-of-the-art performance venues, rehearsal space and county offices.

Funding the project also meant tapping multiple banks and government grant, tax credit and bond programs as part of its elaborate financial structure. That included the use of a $40 million tax credit under the state’s former Economic Redevelopment and Growth program, which was authorized a year earlier by special legislation.

“The diversity of Devco’s portfolio demonstrates its enormous talent,” Cahill said during NBPAC’s grand opening ceremony in September 2019. “Each project may be unique, but each has followed the same Devco path: uncanny preparation, an ability to cull together the financing necessary to accomplish projects others would find impossible to undertake and a driving focus to execute the plan no matter the challenges confronted — always on budget and on time.”

Paladino, who boasts that the performing arts center was delivered with no debt, jokes that “the building part of it is easy.” Rather, the heavy lifting comes in the form of determining the feasibility of the project and creating a business plan.

“Once you know what you want to do and what it costs — and this is usually how it works — then you go shopping,” he said. “Then you go and you try to find the resources.”

Devco does that as well as any developer in New Jersey. And its not-for-profit structure allows it to be much more patient than its for-profit counterparts. The organization’s cash flow is typically from development fees and earned income — accounting for roughly 75 percent of its budget — rather than recurring revenues from completed projects, he said. He added that, in some cases, the company has stayed on to manage a building after it’s delivered, providing another source of income but one that is much smaller by comparison.

“All of our profit gets spent on the next projects,” Paladino said.

Look no further than what’s now known as the New Jersey Innovation and Technology Hub, a planned two-building, 555,000-square-foot research campus in New Brunswick. Devco broke ground on the $665 million project in mid-October, but has spent the better part of five years preparing for it — investing some $4.5 million during that time — from marketing the site to prospective users to razing the hulking, concrete parking deck and retail mall that once occupied the property.

Those efforts are paying off in a big way. The Hub is now proceeding as a key piece of Gov. Phil Murphy’s innovation- and technology-focused economic agenda and will house the new Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, a new Rutgers translational research facility and an innovation center, where startups will mingle with the state’s top health care and academic researchers. Devco is the master developer for a high-powered partnership that includes Rutgers, RWJBarnabas Health and Hackensack Meridian Health, along with Princeton University as the complex’s first tenant.

“If you continue to work on things and you keep your eyes wide open, people see opportunity,” said Paladino, who recalls discussing the site with Murphy when the latter still only a candidate for governor. He also noted that the project, which will help Rutgers fulfill one of its most imminent needs, will benefit from Murphy’s new package of economic incentive programs.

“That makes The Hub the homerun that it’s going to be,” he said.

The groundbreaking came less than three months after Devco’s largest endeavor to date — a 12-story, 520,000-square-foot cancer hospital to be operated by RWJBarnabas Health and the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey. Slated for completion in 2024, the Jack and Sheryl Morris Cancer Center will represent a $700 million investment by its partners — and another manifestation of the developer’s ties to the state’s health care, academic and business community.

It also required Devco to navigate a different kind of challenge. The freestanding cancer hospital will occupy the former site of the Lincoln Annex School, which sparked some backlash among parents and other community members during planning, but construction is now underway on a new facility that will serve as a replacement. RWJBarnabas is paying for the $55 million Blanquita B. Valenti Community School, located about a mile away, as part of its cost for the project, on land donated by developer and RWJBarnabas Board Chair Jack Morris.

Devco still has more to come, even after a banner year. That includes another 500,000 to 750,000 square feet within the next phase of The Hub, which could attract major biotech or pharmaceutical companies or an operator that builds speculative lab space for multiple users. Landing such a tenant would “smooth out and enhance the ecosystem we’re creating,” Paladino said, complementing the medical school, research center and entrepreneurs on the site.

He also noted that Atlantic City Development Corp., the Devco affiliate created in 2015, owns two acres of oceanfront property in Atlantic City. The sites could provide additional expansion capacity for Stockton University, which opened a 533-bed student housing complex and a 56,000-square-foot academic building in the city as a result of the AC Devco-led, $210 million Atlantic City Gateway project completed in 2018. That’s in addition to the project’s second phase, a 416-bed residence hall that Devco now has under construction at Atlantic and South Providence avenues.

“What you have to always appreciate, particularly when you’re doing public-private partnerships, is that you’re often stepping on somebody’s toes from the standpoint of people who work at a university, people who work at a county (who say), ‘Wait a second, this is what I’m supposed to do,’ ” Paladino said. “We had a willing partner at Stockton. This was their first foray into anything like this, so there was some education that had to come along with it.”

While the experience differed in some ways from Devco’s other projects, it also paralleled developments such as the College Avenue campus expansion for Rutgers in New Brunswick and the performing arts center. Aside from the role of academic institutions and nonprofit partners, Paladino pointed to that of influential county executives and public authorities, which helped the developer access tax-exempt bonds to finance the projects.

“There were components of all of those things, and we just refined it every time,” he said.

Devco is now trying to bring that formula to Paterson after being recruited by local stakeholders to spearhead the $47 million, 135,000-square-foot Great Falls redevelopment project. The initiative, which recently secured a critical piece of state funding needed to move forward, calls for components such as the Hamilton Visitor Center at the Great Falls, a 270-space parking garage and a youth center.

“We have been able to take this model and utilize it in different environments that are not always as experienced,” Paladino said. “So sometimes it’s more of a challenge, but it’s more of an educational endeavor than anything else. And I think they look at places like New Brunswick or the work we’ve done in Atlantic City or Newark, and they say, ‘You know, we trust them.’ ”

Devco: A brief history

Seeking to revitalize their company’s home city, a group of Johnson & Johnson executives formed New Brunswick Development Corp. in the mid-1970s to help guide redevelopment in the municipality. Paladino joined the organization as its president in 1994, following four years of working under Gov. Jim Florio and as the deputy director of the Economic Development Authority, with the initial goal of rebuilding an entity that was then teetering financially.

At that point, he recalled, the organization had a dwindling bank account and millions in unsecured debt. And it hadn’t built anything in several years.

“There was a real discussion amongst the existing board at the time about just closing Devco,” said Paladino, who was brought to the role by George Zoffinger, the former Department of Commerce and Economic Development chief under Florio.

By 1998, however, Devco had completed a new 135,000-square-foot administrative office and retail building on George Street for what was then the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey. A year later, it delivered a new Middlesex County administration building on Bayard Street as part of the state’s first privately conceived, planned, developed, constructed and maintained government complex.

The ensuing years brought projects that were progressively more complex and impactful, including a privatized student housing complex for Rutgers, the Heldrich Hotel and Conference Center and the mixed-use, $143 million Gateway transit village, which brought 192 residential units and a new Barnes & Noble Rutgers University bookstore to the heart of the downtown in 2011. That trend has only continued over the past decade, during which Devco has guided multiple projects to completion, delivering for governors from both parties, local officials up and down the state and leaders of universities and hospitals systems.

“Usually you have a couple of things going at a time, and then out of the corner of your eye you see a spark,” Paladino said. “And that’s where you then spend your time and your resources — and your political and financial capital.”

Paladino has taken the journey alongside Executive Vice President Sarah Clarke and Vice President Merissa Buczny, who joined Devco in 1994 and 1995, respectively.

“These are the two people I rely on 175 percent,” he said. “Not only is it stability — it’s that they have evolved and matured and learned, with us all joined at the hip.”