2020 Acquisitions, led by CEO Efrem Gerszberg, has opened the new Old Bridge Golf Club at Rose-Lambertson as part of an agreement tied to the firm’s nine-building, 4.2 million-square-foot industrial development in the township. — Photos by Aaron Houston for Real Estate NJ

By Joshua Burd

Efrem Gerszberg, a veteran developer in the state, jokes that he is “getting old in this business.” But it comes with a serious question for anyone who knows local land use in New Jersey:

“How many times can you fight your way through a town?”

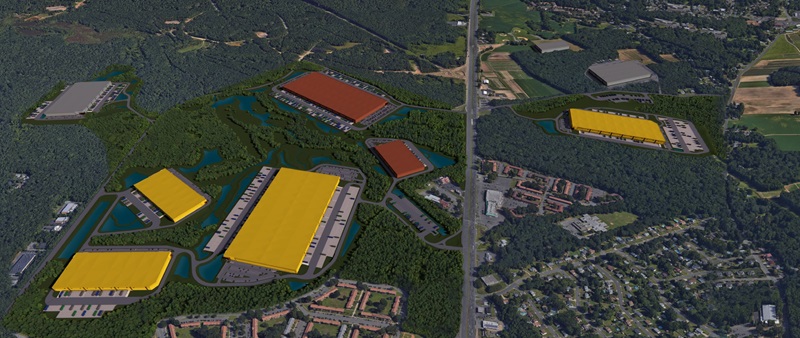

Finding the answer has led to the unique public-private partnership that has taken shape in Old Bridge, where Gerszberg is developing a new nine-building, 4.2 million-square-foot industrial park on Route 9. Just three miles away, his firm has just opened a bucolic, 18-hole public golf course that it planned, funded and built under an agreement with the township — delivering what local officials say is a signature, long-coveted piece of their open space program.

“It’s rare that you’d have almost a thousand acres undeveloped on a major highway in Central Jersey,” said Gerszberg, the CEO and sole principal of 2020 Acquisitions. “So when we looked at the scale of this project, we understood that this is not going to be a traditional project.”

What came next was a story of both good will and good business.

“I had to make sure that it was a no-brainer,” Gerszberg said of his discussions with Old Bridge township officials. “And the easiest way to make it a no-brainer was by giving back.”

The partnership comes in a time of growing tensions between local officials and builders of logistics space across the state, which has weighed on the booming warehouse market in recent months. But 2020 Acquisitions has found a home in Old Bridge for one of the state’s largest projects to date — spanning more than 800 acres — while delivering what it says is New Jersey’s new first public course in two decades.

Gerszberg, who owns two golf courses on Long Island, joined local official recently to unveil the Old Bridge Golf Club at Rose-Lambertson after breaking ground in spring 2022. Designed by Egg Harbor City-based Stephen Kay, the picturesque par 71 course stretches over 218 acres on Lambertson Road, boasting a 30-bay driving range, a high-end miniature golf course and a 6,000-square-foot clubhouse. It’s now open with limited tee times, while it will offer a full schedule starting next spring.

It comes as 2020 Acquisitions prepares to deliver the first phase of its Central 9 Logistics Park at Route 9 and Jake Brown Road, seeking to meet the still-strong demand for industrial space despite a recent pullback from record levels in 2021. The initial offering will span roughly 1.9 million square feet across four buildings a, while the fully built campus will have facilities ranging from 140,000 square feet to some 850,000 square feet, all on a site that is minutes from the New Jersey Turnpike, the Garden State Parkway and other major highways.

“I think this project is one of a handful in the state of New Jersey … where you could put together an area that is not industrial at the time that is so unbelievably located,” Gerszberg said, pointing to storied developments such as Heller Industrial Park and Raritan Center and, more recently, the 4 million-square-foot Linden Logistics Center.

“I thought that we could do the same,” he added. “Once you looked at our access to Route 9, I thought ‘I’ve got to do it all to do it right.’ I also felt that scale almost creates the hub and I felt like one or two buildings wasn’t going to be enough for people to understand how amazing Old Bridge is.”

Gerszberg noted that the assemblage for Central 9 Logistics Park includes the former Glenwood Country Club property. Recognizing that the town was losing a golf course — and seeking to work cooperatively — he pitched the idea of building a new one if the municipality was willing to donate the land. It just so happened that Old Bridge had more than 200 acres at what’s known as the Rose and Lambertson tract, which it had purchased some two decades ago, but had struggled to achieve the long-held goal of building a new municipal golf course.

“When I looked at the property, it was just a phenomenal tract,” said Gerszberg, a member of the renowned Due Process Stable Golf Course in Colts Neck. The plan developed from that point forward, he added, largely in tandem with Steven Mamakis of the Mayor’s Office of Economic Development, and he credits the township with being “very savvy, business-wise,” in that it was not afraid to negotiate but also “understands the economics of projects.” That spawned a plan that incorporated the Rose and Lambertson site into the off-tract improvements for Gerszberg’s industrial park, at a cost of roughly $15 million.

“I need this project because I’m a businessman. They need this project because they need the ratables,” he said. “And with that — it’s impressive — you’re finding a ‘We’re going to work with you to get this done’ attitude.”

The finished product is something that seemingly excites Gerszberg as much or more than 4 million square feet of new warehouse space. He believes the greens at The Rose “are second to none” for a public course, which he showed off recently during a tour of the property.

“We’re talking about every different type of famous greens, from Redan to Biarritz,” he said, adding that his goal was to evoke a midlevel private club.

Importantly, 2020 will manage the course for at least five years with options to do so for as long as 20 years, he said, in order to help maintain the quality of the property while displaying the firm’s long-term commitment. It has hired Ryan McDonald, a former assistant pro at Due Process, to serve as director of golf at The Rose.

“There’s just a tidal wave of excitement from everybody,” McDonald said. “I feel like they’ve been waiting for this for so many years … but now it’s finally here, and it’s fun to watch them walk around the building and see this for the first time.”

“There’s just a tidal wave of excitement from everybody,” McDonald said. “I feel like they’ve been waiting for this for so many years … but now it’s finally here, and it’s fun to watch them walk around the building and see this for the first time.”

Gerszberg also hopes that including both a driving range and miniature golf will help contribute to the property’s long-term success and boost its appeal for the community at large, with plans to program the club with food trucks, live music and other entertainment.

“At the end of the day, I’m a golfer,” he said. “I understand that it’s such a massively small segment of the general population. But if you bring miniature golf, that means that every single kid — and grandfather and grandson and granddaughter — can all play together. Now it becomes a community hub.”

All the while, the firm is developing a massive industrial park that will connect tenants to two interchanges on the New Jersey Turnpike, exits 9 and 11, providing easy access to Port Newark-Elizabeth. Users will also be minutes from large population clusters in every direction, thanks to a highway network that also includes routes 18, 34 and 33.

“I just thought, logistically, it was perfection,” said Gerszberg, who tapped Cushman & Wakefield to market the campus. “And at that point — and I’ve done a lot of development — I understood the scope of what I could do here.”

He also pointed to the opportunity to “ladder the sizes” by providing tenants with options from under 200,000 square feet to more than 800,000 square feet, including the 495,086-square-foot facility that is now online and two other buildings that will deliver by year-end.

That’s not to mention the fact that vacancy will likely remain low in the coming years, amid mounting pushback against new industrial development.

“I think you’ll have a year and a half (with) a lack of new starts,” he said. “So I think that it’s a great time for industrial because eventually over the next, let’s call it 12 to 15 months, that’s when supply will be constrained.”

Old Bridge has already reaped benefits from the project, even beyond the new golf course. Gerszberg cited the more than $17 million in road improvements near routes 9 and 516, while the firm donated $100,000 and land to the fire department to build a new firehouse. Additionally, the Old Bridge school board earned $10 million from the sale of a parcel that accounts for 25 percent of the Central 9 assemblage, while the fully built logistics hub will generate $6 million in annual tax revenue.

Those outcomes, as well as the overall good working relationship with the municipality, have become a point of pride for Gerszberg, who expects it to be “the biggest project I’ll ever do.” Old Bridge Mayor Owen Henry was equally bullish on the public-private collaboration, calling the project historic for the township “because of the monumental task it took for us to be standing here today.”

He also praised Gerszberg for his good will and his follow-through.

“This is going to be here for the current and the future residents and generations of Old Bridge,” Henry said during a ribbon-cutting in late September. “The economic along with the social benefits, far outweigh … anything negative that anyone can say about this project that Efrem has brought to Old Bridge.”