By Morris A. Davis

Since the 1930s, the federal government has actively promoted homeownership as a policy goal. Despite good intentions, our public policy in place after 80-plus years of rules and regulations is not well thought out and poorly motivated. Some days I think we should scrap it all.

I am not opposed to homeownership. To me, homeownership is like flowers: Who doesn’t like flowers? This doesn’t mean that we need federal policy promoting wide-scale flower subsidies.

For the federal government to justify intervention, there should be some compelling reasons that free markets do not produce sufficiently high homeownership rates. The two rationales most frequently cited are (1) homeownership is good for society and (2) homeownership builds wealth for our poorest citizens. To me, these rationales are myths.

Myth 1: Homeownership is good for society

In July, the U.S. homeownership rate was 62.9 percent, its lowest rate since 1965. Is this the socially optimal percentage? I have no idea. There are respectable countries that have lower homeownership rates — for example, Austria (56 percent), Germany (53 percent) and Switzerland (45 percent). And countries with higher homeownership, like Greece (74 percent), Thailand (80 percent) and Russia (84 percent) are probably not great role models for governance. At the aggregate level, there is no obvious link between homeownership rates and well-being.

At the local level, owners likely care more about their community than renters. There are aspects of this that are desirable, such as higher parental involvement in schools. But why would homeowners care more than renters about their community?

Perhaps because, measured at the median, homeowners have two-thirds of their total wealth tied up in their home, whereas a renter has none. Most homeowners have very little portfolio diversification and their total wealth is overly sensitive to small shocks to local house prices. Encouraging this kind of skewed financial portfolio is terrible financial policy and surely can lead to bad outcomes.

Additionally, it naturally leads homeowners to actively restrict new housing supply to keep house prices high. I conjecture that high homeownership rates have played a role in New Jersey’s affordable housing crisis. Our expensive, small houses account for much of our wealth, and many will do anything to keep house prices high — including voting against an increase in the supply of new and affordable homes.

Myth 2: Homeownership builds wealth

There is a great scene in the movie “The Big Short” where Steve Carrell’s character is interviewing an exotic dancer who owns five homes and a condo. The presumed wealth-building in that vignette is built entirely on cheap debt, high leverage and speculation: Put little down, make small payments, let house prices rise and then sell for big profits, baby! I mention this because there are two ways to build wealth with housing: rising house prices or declining mortgage balances. As the foreclosure crisis has taught us, house prices are not guaranteed to rise. The Federal Housing Finance Agency, or FHFA, now publishes data on house price changes at the ZIP code level. I downloaded these data and asked, “What percentage of ZIP codes in New Jersey had real cumulative appreciation above the transaction costs of selling a home?” from 2008 to 2015 and 2003 to 2015.

In other words, if people bought and sold a home in a seven-year period ending in 2015 and a 12-year period ending in 2015, I determine the number of ZIP codes in which homeowners would have made money after accounting for inflation. I assume an inflation rate of 2 percent per year and 7 percent transaction costs, implying the nominal break-even hurdle for positive real house price growth is 23 percent, or 3 percent per year, in the seven-year span and 36 percent, or 2.6 percent per year, in the 12-year span.

For the seven-year period of 2008 to 2015, one ZIP code out of 504 ZIP codes in New Jersey — 07302 — achieved positive real returns for single-family homeowners. From a wealth-building perspective, risk-free Treasury bonds would have produced better returns than housing in New Jersey for 503 out of 504 ZIP codes. For the 12-year period of 2003 to 2015, only 54 ZIP codes — 11 percent — would have achieved positive real net returns for homeowners. Relative to readily available, risk-free, alternative investment vehicles, housing was a poor investment for people living in the vast majority of ZIP codes in New Jersey.

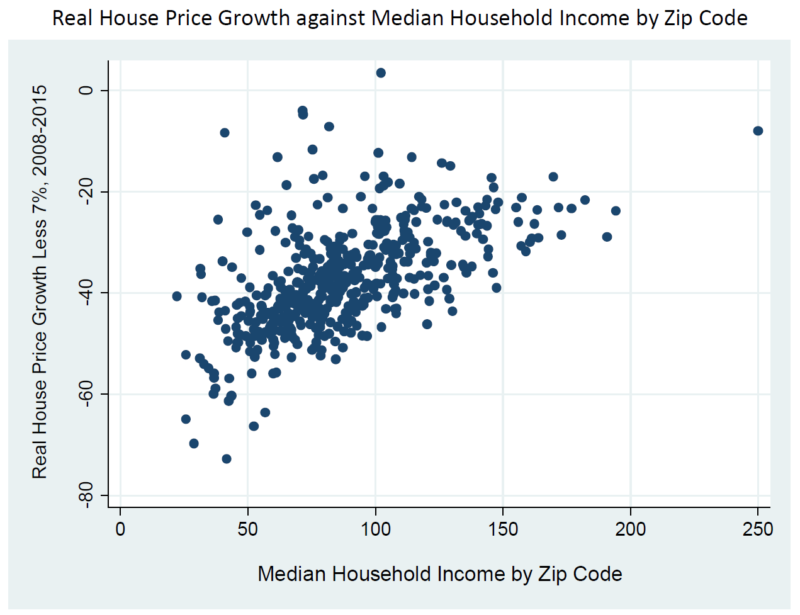

Over the seven- and 12-year periods ending in 2015, housing was an especially bad investment for our poorest citizens. To see this, the graph below plots for each of the 504 ZIP codes in New Jersey the median household income on the X axis and the cumulative real seven-year growth of house prices, less 7 percent transaction fees, on the Y axis. The graph clearly shows a positive relationship: On average, the poorest communities experienced the greatest decline in real house prices. Homeowners in the poorest communities would have lost 50 percent or more in real terms if they had bought and sold over the 2008 to 2015 period, whereas the average loss for homeowners in the richest communities would have been closer to 25 percent.

Of course, there are important caveats and questions to everything reported here: Should we care about real versus nominal returns? Why just look at seven- and 12- year growth ending in 2015? My point is not that housing is uniformly a bad investment. Rather, house prices are risky: House prices are not guaranteed to rise and, in many times and places, housing is a bad investment.

Of course, there are important caveats and questions to everything reported here: Should we care about real versus nominal returns? Why just look at seven- and 12- year growth ending in 2015? My point is not that housing is uniformly a bad investment. Rather, house prices are risky: House prices are not guaranteed to rise and, in many times and places, housing is a bad investment.

The other way in which housing can build wealth is through the amortization of mortgage debt.

I guess this is correct, except for the fact that, in the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage — the most widely used mortgage product — amortization occurs very slowly. For example, at current market rates, only 14 percent of the mortgage balance of a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage is paid off after seven years. Ultimately, paying down a mortgage is just a form of saving, and there are lots of ways in which people can save if they want to.

Exploding public policy

For the purpose of boosting the homeownership rate, the federal government has two policies in place that affect the pricing and availability of mortgages: the mortgage interest tax deduction and subsidies for mortgages to lower-income borrowers via subsidized loan guarantees from the Federal Housing Administration, or FHA, and other government agencies.

These are bad policies. The mortgage interest tax deduction is a tax break to those that are relatively affluent. Data from the IRS suggests that the top 20 percent of taxpayers account for two-thirds of mortgage interest deducted. If this tax break is eliminated, households currently benefiting from this tax break will continue to own, although they might choose to own less expensive housing.

The subsidies provided by the FHA are more harmful. These words are harsh, but a straightforward reading of the facts suggests the FHA is engaged in irresponsible and possibly predatory lending. Here is a summary of the business model: The FHA provides people that have almost no equity and a poor credit history with a heavily subsidized mortgage in order to buy a risky house they cannot afford. My evidence?

No equity: The typical down payment on an FHA home purchase loan is 3.5 percent. Additionally, the FHA loan is almost always a 30-year fixed-rate product, so it has little amortization over the first five to seven years.

Poor credit history: FHA lending currently accounts for 84 percent of all loans made to borrowers with a FICO score between 580 and 660, a credit score range associated with subprime lending during the housing boom.

Affordability: More than 45 percent of all FHA loans have a payment-to-income ratio, or DTI, of greater than 43 percent — the limit set for private-sector lenders under the Dodd-Frank ability-to-repay rules — and some FHA loans have a DTI of more than 50 percent.

Do we really want the working poor to assume a highly levered position in a very risky asset with a mortgage characterized by slow amortization and unaffordable payments? Because this is current government policy. It seems crazy to me.

Final thoughts

I am not suggesting that markets always produce the most desirable outcomes with respect to housing. And, I think we can craft policies that help the working poor own a house within their means if homeownership is a desirable policy goal, which perhaps it should be. But our current policies are wasteful and inefficient at best and have been destructive at worst. It is time for a change.

Morris A. Davis, PhD., is the Paul V. Profeta chair in real estate and academic director at the Rutgers Business School Center for Real Estate.